Techno-Consumer Paradigms

A framework for thinking about consumer internet

Welcome to the third edition of Black Box. Last time, I wrapped up a two-parter on the future of content. This time, we’ll be looking at consumer internet.

There are three curves that come up repeatedly in tech. If you’re reading this, you’re probably familiar with the technology adoption lifecycle. The related Gartner hype cycle is often referenced in the same discussion. But unless you spend a lot of time on VC Twitter, you probably haven’t heard of techno-economic paradigms (TEPs). This is because, unlike the other two curves, TEPs originate in academia; they are the work of economist Carlota Perez. TEPs attempt to explain how innovation drives technological, institutional, and financial changes, which in turn create cycles of economic growth and crisis. The theory goes pretty deep1, but you can get the basic idea from the graph above.

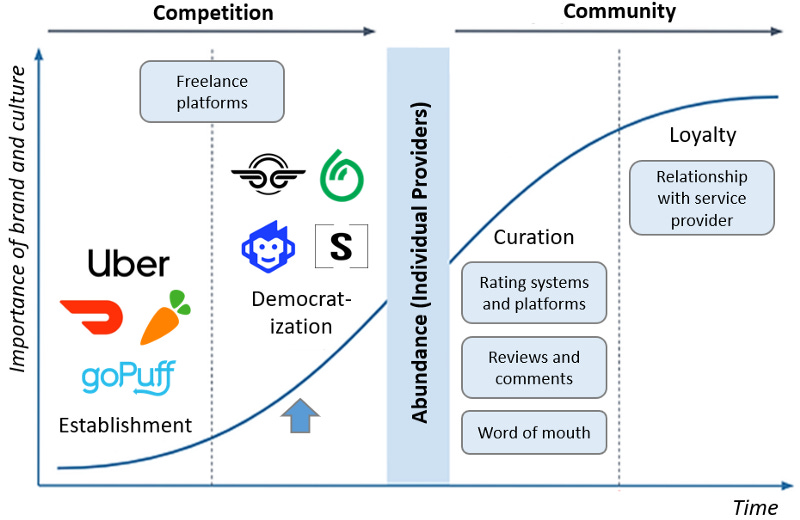

TEPs are not the subject of this essay, but I bring them up because I have noticed similar behavior in consumer internet from the perspective of brand and culture. I believe these techno-consumer paradigms (TCPs) can explain how verticals within consumer internet evolve, and therefore help identify startup and investment opportunities.

Technology and Abundance

Key to understanding TCPs is the theory of abundance, as laid out by Shopify’s Alex Danco. To summarize,

“Capitalism, at its core, is fairly straightforward: create shareholder value by providing customers with access to something scarce.”

“Technology increases access to what is scarce” (e.g., by making goods more available or less expensive).

“Abundance is the condition reached when the friction involved in consumption decisions approaches zero.”

TCPs are created by the internet enabling a new mode of consumption or business model (or both). They are initially defined by scarcity as a few companies centralize the market in the Establishment stage. Given their market power, these incumbents rarely worry about brand and culture. As the pie grows, more companies want a piece. In the Democratization stage, “shovel” companies develop tech to help these upstarts break into the market. The number of new entrants explodes, forcing them to compete with the old guard and each other; brand and culture become important ways to stand out. This influx inevitably leads to a state of abundance.

In response, companies transition to helping consumers find the best option for them in the Curation stage. This effectively reintroduces some scarcity. The shift in “consumer” as the masses to individuals naturally puts a spotlight on brand and culture. Successful companies will develop communities, whether organically or actively. As these communities grow in the Loyalty stage, companies will turn their focus to promoting brand and culture through a continuous stream of content, interactions, and incentives. While this “drip” strategy keeps consumers engaged and competition limited over the long term, it can be hard to manage. Some verticals will require tech to help implement these programs.

E-Commerce TCP

The e-commerce TCP is the easiest to see given its simplicity and relative maturity. The Establishment stage is Amazon. About a decade after its founding, e-commerce became big enough that others wanted in. Etsy was a crack in the wall that allowed individuals to participate, but the floodgates really opened when Shopify started “arming the rebels” for actual companies. The Democratization stage has since grown into an ecosystem of third-party services and APIs that abstract every link in the e-commerce value chain. This modularization significantly lowered the barriers of entry for everyone; as Danco points out, “when every rebel is armed, none really is”. The resulting abundance can be seen in the number of and physical similarity between DTC products. (Just look at how many DTC beverages there are, and how all of them are in pastel cans with san serif logos2.)

This physical similarity is not accidental; once a product achieves even minor success, contract manufacturers will quickly turnaround replicas that anyone can buy wholesale on Alibaba3. Most DTC companies don’t have proprietary technology, so the only moat available to them is their brand. Brand building has transformed some e-commerce companies into pseudo-media groups in the Curation stage. For example, Glossier and The Hundreds are known as much for their perspectives on culture and style as they are for their products. Other companies, like Curated and Thingtesting, act purely as navigators of these stories and values. Accordingly, their value propositions are completed based on the brand and cultural expertise of their guides and reviewers.

The Loyalty stage in e-commerce is boring on one hand because consumer goods has long focused on loyalty. On the other hand, the ability to tokenize loyalty unlocks a lot of new ways for brands to reward and interact with their customers, such as token-gated access to cultural events4. While loyalty tokens have a lot of promise, I believe it is still too early to be building and investing in them. Web3 adoption and gas fees aside, I don’t think the Curation stage has finished playing out. The number of DTC companies continues to grow, and iOS 14 has made it harder for them to acquire customers through ads alone. More than ever, consumers will need curation to find the best products for them. Conversely, traditional loyalty programs work well as-is, making loyalty tokens a less urgent “good to great” improvement.

Creator Economy TCP

The creator economy TCP is the next easiest to understand as many of us have personally participated in it. The Establishment stage are the gatekeepers of old media: publishers, studios, and record labels. The first time regular people could create and monetize content was on social media, but the money it made was going to the platforms instead of to them. Youtube marked the start of the Democratization stage when it began sharing ad revenue with creators in 2007. As creators developed followings, they turned to Patreon and other paywall companies to capture more value from their personal brands and culture. The possibility of monetizing audiences directly improved creator economics by reducing the number of fans needed for content to be at least a side hustle, encouraging more people to become creators. Unsurprisingly, we have an abundance of content.

Curiously, the creator economy has made little progress towards the Curation stage despite tremendous need for it. This is reflected in the fact that TikTok’s stunning success is widely attributed to its recommendation algorithm. Yet the creator economy is already innovating in the Loyalty stage with creator tokens, the case for which I previously wrote about. This puts additional pressure on curation, since audiences need to discover the creators they want to be loyal to in order for creator tokens to realize their full potential.

Curation technology is therefore the biggest opportunity in the creator economy right now. Startups and investments are starting to emerge in this space: Medal.tv recently raised a $60 million series C to help gaming creators automatically capture highlights, and Breakr closed a $4.2 million seed round last July to connect up-and-coming musicians with social media influencers for exposure and feedback. But many more curation companies are needed to help us process this ocean of content. Furthermore, they need to keep brand and curation top of mind since curation means creators have less time to make an impression. Successful curation condenses and magnifies what makes a creator unique.

Internet-Enabled Services TCP

The internet-enabled services TCP is the most opaque and least developed, in part because services are hard to put online. The gig economy companies that make up the Establishment stage were able to do so only by explicitly avoiding brand and culture — their model requires service to be a commodity. But this has major disadvantages to all sides. On the platform side, commodity service makes it easier for competitors to enter the market by standardizing worker acquisition and onboarding, service pricing, and customer expectations. On the provider side, commodity service gives platforms significant power in wages and labor issues since workers are perfect substitutes of each other. On the customer side, commodity services makes fulfilling bespoke requests an exception rather than the rule.

Freelance platforms like Upwork and Fiverr began to break this mold because the services they offer often involve creative work (e.g., website design) and therefore inherently differentiated providers. But it wasn’t until the late 2010s that internet-enabled services entered the Democratization stage. That was when Squire, Shopmonkey, and Dumpling pioneered the business-in-a-box model, which gives workers the operating and business stack to start their own service companies and charge what they think is fair. But this freedom also means competition as more workers strike out on their own. Providers will have to build their brand and culture to stand out. For example, some Dumpling shoppers could specialize in ethnic foods while others may advertise their familiarity with certain diet restrictions.

Given how recently internet-enabled services entered the Democratization stage, I don’t think we will have an abundance of individual providers any time soon. If anything, more business-in-a-box companies need to be built, and they need to make it as easy as possible for workers to highlight their brand and culture. Services have always had curation mechanisms, whether it be rating systems and platforms, reviews and comments, or word of mouth. Successful workers must be able to provide exceptional service or something special to be successful in the Curation stage. And as the nameless Instacart shopper becomes Jon or Isabelle (who happens to use Dumpling), I suspect a customer’s relationship with their service providers will be the basis for the Loyalty stage.

TCPs also exist in other consumer internet verticals, but I’ll stop here. I hope they are a useful framework for thinking about where the next startup and investment opportunities lie in this space. ∎

Do you agree with this framework? Would especially love to hear from operators and investors in this space—tweet your thoughts @jwang_18. See you in two weeks!

I recommend this excellent overview for those interested.

Sharp-eyed readers may notice that even their URLs are similar: four of the six websites are drinkbrand.com.

This is a manifestation of Hotelling's Law. Since DTC companies cannot differentiate on product, they differentiate on the added dimension of brand and culture.

There are also mechanical advantages to using loyalty tokens, but I don't think brands would want to increase the liquidity of their points since that would reduce the loyalty they are supposed to cultivate. The benefit has to come from brand and culture.

I have a question, as probably I have not understood the framework. In the example of e-commerce, Amazon started not paying attention to brand, and creating a market itself. But they have not stayed there, they have evolved too. To me they have a strong brand and a strong loyalty (prime program is a success case).

My doubt/question is, how do you represent this evolution in the proposed framework?

many thanks

Hello, thank you for your work. It really resonated with me with the Wardley Maps for looking at a company's business strategy. In your case, I love the adaptation of the creator's economics.

https://medium.com/wardleymaps/on-being-lost-2ef5f05eb1ec