Welcome to the seventh edition of Black Box. Apologies for missing the last post; work blew up unexpectedly and I called an audible. Speaking of, this post synthesizes the themes I’ve written about so far into a unified thesis.

My freshman seminar was taught by a professor we nicknamed Umbridge due to her severity and stature. Analogous to her Hogwarts counterpart, she had strong views on writing which she impressed on us — not that anyone dared challenge her after she threw an offending paper out of a window. One of her iron rules was shunning “nothing words”, which in her class included not only good and bad, but also society and truth. (Did I mention she was opinionated?)

Among the condemned was culture, which has featured in every article I have written so far. Yet I have never defined culture (and it does have a meaning, in spite of Professor Umbridge) nor explained why consumer tech should care. I will do so now.

I view culture as any widely understood and persistent yet adaptable form of interaction between people. Each of these parts is critical:

Widely understood, because culture is information and information has value only if people recognize and appreciate its meaning. More precisely, information becomes culture when the density of people who understand its meaning is sufficiently high within a group (i.e., does not have to be literally everyone).

Persistent, because information is culture only if people repeatedly use or reference it. This also helps the information spread by effectively teaching unfamiliar witnesses, creating a virtuous cycle commonly called virality. Information also benefits from the Lindy effect since the longer it is in use or reference, the longer it is relevant.

Adaptable, because people can use or reference culture repeatedly only if it can be customized to their interests or modified to fit new situations. In other words, people must be able to participate and create culture for the underlying information to evolve. And like a living thing, information that does not evolve does not survive.

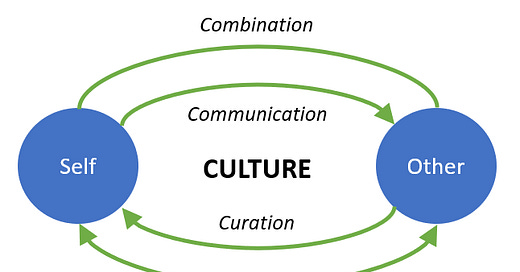

The way I think about culture borrows the concept of directed and undirected edges from graph theory. Analyzing all the possible interactions that people can have with each other is a hard problem, so instead I abstract everyone to just two people, Self and Other. It is then easy to see culture can take on only four forms of interaction:

Combination. Much of culture, especially pop culture, is the combination of existing ideas with new ideas. Memes, fanfic, sampling, mods, and parodies are all examples of this. (Graph theoretically, combination is an undirected edge because it happens spontaneously and spreads indirectly.)

Consumer tech should care about combination because successful consumer startups need to not just embrace it, but take advantage of it. In “The Future of Content is Public or Token-Gated”, I argued that mass media should make its IP freely available to consumers so the content remains relevant for longer. As people remix, the original content’s value will increase and IP owners can grow their “off-content” monetization through ads, tickets, merchandise, etc.

Communication. We are constantly using culture to signal something about ourselves. Fashion is the most obvious example, but almost any product that is not a commodity has some cultural meaning (e.g., organic, fair trade, cruelty-free). This kind of communication is not limited to physical things — it is why blue is masculine and pink is feminine, why French is considered the language of love but a British accent sounds more attractive, and why people spend hundreds of thousands of dollars to attend certain universities.

Consumer tech should care about communication because consumer startups must help people do it better to win. As I explained in “The Novelty Effect”, Cameo is successful because celebrity video shoutouts highlight the qualities that make recipients unique. They also create the illusion that givers know the celebrities and called in huge favors so that recipients could share the cultural spotlight with their favorite famous people for a few minutes.

Curation. On the flip side, it is increasingly difficult to know what we should communicate. Trends change in an instant, products all look the same, and the flood of content never stops. We need influencers, reviews, and outfit of the day videos to help us sort through and make meaning of all this.

Consumer tech should care about curation because some of the most valuable consumer startups right now are curation companies, and there is opportunity for many more. I flesh out this idea in “Techno-Consumer Paradigms”, but it is easy to get the gist from this visual:

Coordination. The most structured form of culture, coordination is the multi-player form of combination. Coordination is relatively rare because incentive alignment is hard, but its cultural and financial potential is also much higher. As a result, songs with featured artists and brand collaborations are becoming more the norm than the exception.

Consumer tech should care about coordination because any consumer future, especially a web3 one, will heavily feature it. Building out the infrastructure to support coordination is the next big thing in consumer, and startups in this space should remember the principles I outline in “Social Decentralization is a Design Outcome, Not a Blockchain Feature” regardless of their web version.

To answer the title, culture matters because consumers are cultural creatures. The value of consumer tech therefore derives from enabling or facilitating the interactions described above. Successful consumer startups will figure out a way to do so that is better than (or at least different from) both the status quo and competitors. In other words, their winning insights are as likely cultural as they are technological. So while nothing words have no place in freshmen seminars, they should have a central place in founders’ minds. ∎

Does this framework reflect your experience or a bit too woo? Let me know what you think @jwang_18. See you in two weeks!

This is spot on! Monolithic thinking usually leads to narrow roads that not only get crowded but also lead to nowhere. I have always believed that great companies oftentimes treat technology as a means to an end, rather than an end in itself.